Strong Women Who Stay in Their Cages

A Commentary on Strength, Subjugation, and Self-Discovery in a Mormon Woman's World

I’ve been thinking about the nature of Mormon women. (Meaning that I’ve been trying to understand myself, even though the last time I called myself a Mormon was more than a decade ago.) As I’ve been writing my memoir, I’ve found it necessary to weave some church history into my narrative because it just explains SO MUCH about how I got into that sham of a marriage, why I stayed for so long, and how I finally got out. The history I discovered is far more personal than I expected it to be. I spent two weeks last month in the rabbit holes of family, Mormon, and US History—cross-referencing stories of my great-great grandparents with the Mormon Migration, the Civil War, Utah territorial politics, Women’s Suffrage, and the end of polygamy.

What I found made me more proud than ever to be the last link in my personal chain of Mormon women. It’s a contradiction, I know. I would never—could never—go back. I would never raise my daughter in the faith. But there’s something mesmerizing about that line of resilient, educated, gritty, fascinating, tough-as-nails women who stayed in the cages of this intensely patriarchal, highly demanding, and psychologically harmful religion.

Let me explain.

In 1870, fifty years before the 19th amendment was passed, Congress authorized the Wyoming and Utah territories to test women’s suffrage. Although Wyoming technically became the first territory to enfranchise women, it was the women in Utah who would first exercise the right to vote. The new law vested as many as 43,000 women in the territory (around forty times the number of enfranchised women in Wyoming).

The experiment in Utah received intense national attention but for reasons that might surprise you. The question that preoccupied the minds of reformers on the East Coast wasn’t whether women’s suffrage would work, but whether the women of Utah, once awarded the vote, would throw off the shackles of that “twin relic of barbarism,” polygamy. As one Christian worker predicted the situation for the Chicago Advance: if the women were left to themselves nine-tenths of them "would vote it so thoroughly out of existence that it would never be heard of again.”1 Even the National Woman Suffrage Association at its 1870 convention resolved that the enfranchisement of Utah women was the one safe, sure, and swift means to abolish polygamy in that territory.

But they were all wrong. The women of Utah didn’t make a single step toward ending polygamy. Instead, they staunchly defended it.

The practice wouldn’t be abolished until the Federal Government strong-armed the Mormon Church into submission some fifteen years later, first by making polygamy a federal crime, then by a series of crackdowns on the freedoms and power of the Church and its members in the Edmunds Tucker Act of 1887, which included disincorporating the church, seizing its property, replacing local judges with federal judges, requiring an anti-polygamy oath to vote, hold public office, or serve on a jury, and finally stripping women of the right to vote that they had enjoyed for the last seventeen years. To the women of Utah, it was an obvious punishment for dashing the hopes of US politicians that the women would do the dirty work of abolishing polygamy.

The Women’s Exponent, written and run by Utah women, many of them simultaneous polygamists and suffragettes, (figure that one out for me) published eloquently scathing rebukes to the assumptions made by their compatriots on the East Coast that Mormon women under the yoke of polygamy were ignorant, degraded, and slavish in their obedience2. The Exponent characterized the Edmunds-Tucker Act and its predecessors as “wicked and cruel laws to destroy our religion, to break up our families, and bring ruin, desolation, and woe to our happy homes.”3

They must have been confuzzled and discombobulated—those enlightened liberals of the East. But they misunderstood something fundamental to the ethos of Mormon Women—their honor.

The idea can be summed up in a famous quote by Karl G Maeser, a prominent educator and member of the Mormon Church. Students of BYU know his name, inscribed on the oldest building on campus, a Greek revival edifice, reminiscent of the Ivy Leagues with its tall marble columns and a statue of Karl G. Maeser himself outside of the building.

“I have been asked what I mean by “word of honor.” I will tell you. Place me behind prison walls—walls of stone ever so high, ever so thick, reaching ever so far into the ground—there is a possibility that in some way or another I might be able to escape; but stand me on the floor and draw a chalk line around me and have me give my word of honor never to cross it. Can I get out of that circle? No, never! I’d die first.”

I remember my freshman year at BYU—the pamphlet I received with my acceptance packet outlining BYU’s “Honor Code”—a set of rules stricter than almost any American institution of higher education in the nation. I had to sign the Honor Code if I wanted to be a BYU student. It wasn’t optional. With that commitment, I promised to keep to a whole host of standards—never to cheat on tests, never to drink alcohol, smoke, or do drugs, never to wear shorts above the knees or shirts without proper sleeves, and never to allow a boy into my bedroom, let alone engage in tomfoolery.

Many college co-eds would see the BYU Honor Code as overly strict. But I didn’t. Mormons, after all, are a covenant people. We are used to “making and keeping sacred covenants.” Covenants are more than promises. They are two-way agreements with God, and a true Mormon would rather die than break a covenant.

The whole “death” part of covenant-making was, of course, in my mind, metaphorical. I only knew that the promises I made as a Mormon were protected by my own chalk circle of honor. By the time I went to the temple for my first endowment ceremony in 2000, the church had already quietly removed from the endowment ceremony all of the penalties associated with the vows of secrecy I would take there. I never knew about the rooms full of people simultaneously pantomiming the various gruesome punishments for loose lips—a thumb drawn across the throat as if with a knife, a hand cupping under the heart as if to receive the organ torn from the breast, the slicing motion of the hand from the left hip to the right, symbolizing disembowelment.

But my great-grandmothers on both sides of my family would have. On my father’s side, my great-great grandmother Christina received her endowment in 1865 in the Endowment House, a temporary temple that early Utah settlers used for sacred ceremonies such as baptisms for the dead, washings and anointings, the endowment ceremony and “sealings”—the Mormon word for a marriage ceremony for “time and all eternity”.

On my mother’s side, my great-great grandmother Diantha received her endowment in Nauvoo. She was an early convert to the church, along with her husband Titus, the first of Sidney Rigdon’s Revivalist congregation to raise their hands when he called for volunteers to step into the waters of baptism. Diantha was good friends with Joseph and Emma Smith, and I learned in my rabbit hole wanderings, that both the garments all temple-endowed Mormons wear, as well as the green apron with the embroidered fig leaves worn in the Endowment Ceremony, were first designed and sewn by Diantha at the request of the Prophet Joseph Smith.

My roots go deep.

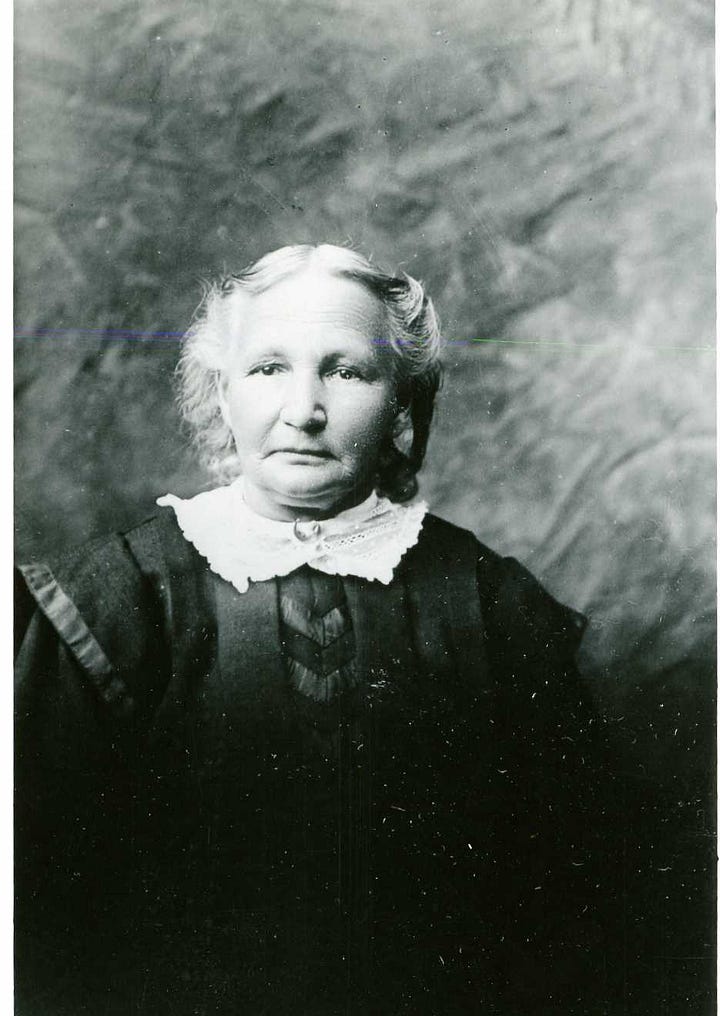

So when I read the words of The Women’s Exponent defending polygamy, I saw myself. When I read a letter from Christina, written to her daughter in 1880 and deposited in a “treasure chest” in Salt Lake City to be opened fifty years later, in 1930, I heard my own voice.

“I feel to bear my testimony to this being the work of God, for I have been led through many crooked paths in safety and have proven the truth of this work. I know that plural marriage is one of the most purifying and elevating principles in our holy religion. I pray that I may prove faithful to the end.”

Christina, like so many Mormon women, was an enigma. A paradox. I knew that she was a plural wife. But I would later learn that she was also a midwife, editor of her local newspaper, a Relief Society President for twenty-five years, a poet, and a women’s rights activist. Two years ago I discovered a poem she wrote (presumably after the Edmunds Tucker Act stripped her of her right to vote).

“How often I think of the time fast approaching

When women will stand as the equal of men.

When the bright sun of freedom will shine without scorching

And clear up the muddles that cloud the men’s brain.”

I wonder. Was her brain muddled just as badly—a victim of brainwashing? Could she not see that it was not just the Federal Government that stripped her of her freedom, but her religion also that held her in chains? This witty, strong, intelligent woman could not even see the walls of her own prison.

I certainly couldn’t.

I remember feeling so empowered as a woman in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. See? Look how women have the greater gift of giving life, and men only have the consolation prize of Priesthood Authority and decision-making power over every aspect of church administration. Look how we are encouraged to get an education and develop our talents, even if the only reason is to be better mothers and wives. Look how we get to speak and pray in Sacrament Meeting and General Conference, even if the ratio of male speakers to female is 7 to 1.4

Look how we women have our own organization—the Relief Society—that we get to lead all by ourselves. (Sort of.) Organized by Joseph Smith himself, the Relief Society stands as proof positive for Mormon women that Joseph Smith was definitely a feminist ally and definitely not a womanizer.

But then I watched the HBO Series, “The Vow” in which the self-improvement cult NXIVM, led by a super creepy narcissist named Keith Rainere, gave the women in his organization their own society as well, ostensibly for their female empowerment and self-governance. The organization, called DOS (an acronym for Dominus Obsequious Sororium—loosely translated from the Latin as Master Over Obedient Sisters), was a secret society—a multi-level pyramid of masters and slaves—women leading (i.e. controlling) women. DOS lured an absurd number of highly intelligent, talented women into its ranks before one of the “higher-ups” in the organization, Sarah Edmonson5, was branded with the initials of Keith Rainere and blew the whistle. (Yes, I said branded. By other women. With a hot iron.) It was then that she realized that DOS had a shadow master, and it wasn’t a woman.

And then my mind exploded. I thought about Christina, and how as a first wife, she benefitted from the addition of a second. Her sister wife was a 16-year-old girl named Hattie, who had walked across the plains as a child. As the story goes, when William T. asked Christina how she felt about him taking a plural wife, Christina answered, “If Hattie can get along with us it is alright with me.”

The addition of Hattie to the family enabled Christina to grow beyond the demands of hearth and home. When Christina left in the horse-drawn wagon to attend a Relief Society meeting, a birth, or to get medical training down in Salt Lake, it was Hattie who kept the home fires burning. They loved each other, to be certain. To the day they died, they would profess a deep sisterly alliance, even to the point of ganging up against William T. in the event of a disagreement. But there is no doubt in my mind that in the hierarchy of Mormon patriarchal culture, Christina was a master, and Hattie a slave.

And then I thought of the Handmaid’s Tale. And 1984. And the Hunger Games. And my own life. And every other dystopian story of shadow masters and self-policed prisons and people who cannot see the forces that really pull the strings.

This is how you keep strong women in cages. You feed them stories of freedom and empowerment. You hide the truth—that they are slaves to a shadow master. Livestock to be branded with covenants and promises, new names and anointings as Queens and Priestesses. Breeders for the cause. You tell them of honor. You give them status and belonging and power over another. Then you don’t even need to lock them up. You can hand them the key and they will stay. Even in front of an open door. The way I did until I woke up.

Quote in Woman Suffrage in Territorial Utah by Beverly Beeton in the Utah Historical Quarterly, p. 103

Anna Dickinson, an American orator and lecturer and an advocate for the abolition of slavery and for women's rights, gave her famous “Whited Sepulchres” speech before Congress and published the same in the New York Times after a visit to Salt Lake City. Her speech, which she gave all over the country, popularized the image of the “degraded” Utah women.

Sarah wrote about her journey into and out of the cult in her memoir, “Scarred” and now runs one of my favorite podcasts, “A Little Bit Culty.”

This is so powerful.

I can’t wait to speak with our ancestors and find out how they really felt about their situation in early Utah.

This is such a powerful piece. Of course there is strategy and when the depth of history allows it to expand, it becomes harder and harder to end.

And, to the point of the women not denouncing polygamy, I remember when my former husband remarried. My kids thought I’d be jealous, but I was relieved. It meant less of his negative energy focused at me. A freedom of sorts. I can understand the freedom they might of felt within the confines of the system.